Professor extraordinarius

Ten years ago, the world of Andrzej Dłużniewski, an acclaimed avant-garde artist, faded to black. It wasn't his fault. The car he was driving was hit by a lorry. In the accident he lost his eyesight.

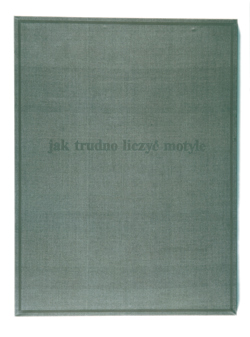

Andrzej Dłużniewski can't be labeled as a painter, sculptor, performer or writer. He does it all. In his art, the essence comes before the form. He always speaks of art as a mental thing. His works tend to be crude, void of dazzling displays of skill. Instead, they are a display of thought, a kind of riddles. Like, for example, a gray canvas on which he wrote, with a slightly darker shade of grey, the words: so hard to count butterflies.

A mark left by a painting

Andrzej Dłużniewski studied architecture and philosophy but ultimately he graduated from the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts where he studied sculpture. In 1970 he was elected to a fellowship there and set up a Workshop of Intermedias. What exactly are intermedias?

- Intermedia is a space between – explains the professor – It fills the spaces left by the conventional disciplines. It tries to capture what you cannot render in painting, photography or sculpture. It explores these spaces between, which are full of meaning and emotion and can't be ignored. It is a disciple shaped by the artist as there are no established conventions and formulas there.

The work he prepared for his master thesis was also of an intermedia kind – a series of photographs showing a big „sandbox” filled with dry sand out of which he had fashioned various landscapes. The work raised much controversy among the faculty but after a long debate they decided that such approach to sculpture was acceptable. Then it got even more unconventional with „A copy of a painting of a copy of a painting of a copy of a reproduction of a painting of a reproduction of a painting” or „A mark left by a painting” (a photograph of a mark left by a painting removed from the wall).

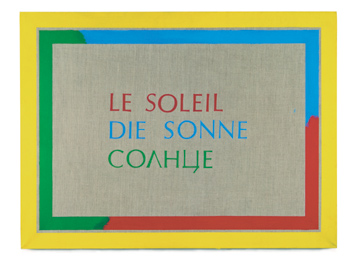

He also explored the relations between the meaning of words and

their grammatical gender in various languages and rendered the

results of his studies on canvas, using three coulours.

- The most prominent characteristic of Dłużniewski's art is its

conceptual origin, its intellectual foundation, which were

important in the early 70's, when a new tendency in art, called

conceptual art, was flourishing – states Wojciech Krukowski, the

director of the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw and

Dłużniewski's friend – For conceptualists the most important was

the idea and the intellectual motivation behind a work of art.

There's no room for a psychological or an expressive reaction.

Intermedia, conceptual art and many other things were discussed in Dłużniewscy's flat on Piwna Street which was an important centre of the artistic community in the 80's and the 90's.

Words

„1998 was for me a year of transition. All of a sudden many of

the things I considered wise seemed stupid and the other way round

– I found traces of wisdom in things most absurd” - these are the

opening lines of „Odlot”, a collection of humorous stories

published by Dłużniewski in 2000. He had written them two years

earlier after having lost his desperate struggle to retain his

eyesight.

- It was during the first year of my disability – he recalls – I

then decided, perhaps instinctively, to start writing, as it seemed

no longer possible to pursue the visual arts, which were always my

speciality. I had to look back, to re-evaluate things. Most of my

life I wasn't blind, I experienced the world through images. For

most people it would be a tragedy but I didn't want it to be so in

my case.

The characters of „Odlot” are: Dłużniewski himself, Mr Zbynio

the stoic and the least likeable of the three, the professor. The

three personas are different facets of Dłużniewski's personality

and they are constantly engaged in never-ending disputes.

Writing proved an excellent therapy. True to form, professor

Dłużniewski presents his own, ironic and humorous account of

it:

- I used to write on separate sheets of paper, using my knee for a

desk. I sometimes wrote one thing on top of the other and my wife

had hard time deciphering it. Once I wrote several pages without

realising that my pen had run out. But I was pressing so hard that

I literally engraved the words on the paper so we smeared it with

graphite and managed to read the text.

Geonauts

„They have arrived recently and won't stay long. The purpose of

their visit is quite simple. They didn't come here to conquer, to

exploit or to learn. They simply wish to see whether their presence

and their lifestyle bother the natives. Since they've found that is

the case they are preparing to leave and won't stay long” - that's

how Prof. Dłużniewski describes Geonauts in his book. Geonauts are

hundreds of small bronze figures, sitting on large white

pedestals.

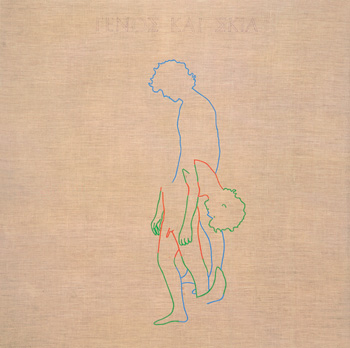

- After the accident my fellow colleagues the sculptors, eager to

help me, brought me some wax. I'd never worked with wax before – he

relates – I started making these little figures. After I'd made a

whole bunch of them they were cast in bronze. Everyone said they

looked quite smart.

His collegues from the Academy of Fine Arts probably didn't even

realise how much help they were.

Although initially it was just a form of therapy, it stirred up a

new creative potential in him – says Wojciech Krukowski – His

intellectual faculty of an artist accommodated very easily and

embraced this new form of creation.

The Academy also reacted very sympathetically and made no

objections when Prof. Dłużniewski decided to go back to

lecturing.

- I didn't think I would be able to work at the Academy again – he

admits – It was possible because we always used to spend most of

the time speaking to students, so I still speak with them. The

visual aspect of their work is supervised by my assistant. The

results vary, but it's all right, as long as it makes any sense,

because sense is something we can talk about.

1 Consistent Street

„Geonauts”, „Odlot” and lecturing at the Academy proved an

excellent therapy. Dłużniewski is an active and exhibiting artist

once again. Whenever he wants something painted, he can always

count on his wife, Emilia Małgorzata, who is a painter and on a

young artist named Maciej Sawicki.

- I just sit on a couch and tell everyone what to do – he says with

a laugh. He's still unconventional, inconsistent and in good form –

Consistency frightens me – he explains – I've once come to a

conclusion that if there was Consistency Street in my mind's

landscape, it would be a very short one, one block long

probably.

Being consistently inconsistent, he has recently disassembled an

old chessboard to create some absurd compositions. He is also

writing stories about a cat and a rabbit. He sometimes even forgets

he's blind.

- I can't say I'm happy with the situation, although I pretend to

be – he says and adds – That's just the way it is. It's different.

Only now it's hard to count butterflies...

Artykuł powstał w ramach projektu "Integracja

- Praca. Wydawnicza kampania informacyjno-promocyjna"

współfinansowanego z Europejskiego Funduszu Społecznego w ramach

Sektorowego Programu Operacyjnego Rozwój Zasobów Ludzkich.

Komentarze

brak komentarzy

Polecamy

Co nowego

- W 2025 roku nowe kryteria dochodowe w pomocy społecznej

- Rehabilitacja lecznicza Zakładu Ubezpieczeń Społecznych. O czym warto wiedzieć

- Czego szukają pod choinką paralimpijczycy?

- Gorąca zupa, odzież na zmianę – każdego dnia pomoc w „autobusie SOS”

- Bożenna Hołownia: Chcemy ograniczyć sytuacje, gdy ktoś zostaje pozbawiony prawa do samodzielnego podejmowania decyzji

![kadr z filmu My skrajnie otyli [FILM]](/files/nowe.niepelnosprawni.pl/public/2024/thumbnail_gajda_youtube_nowe.jpg)

Dodaj komentarz